MAJOR REGULATORY REVIEW PROCESSES FOR THE WASTE ISOLATION PILOT PLANT: A PERSPECTIVE FROM THE APPLICANT

James Mewhinney and Craig Snider

U.S. Department of Energy, Carlsbad Area Office

P.O. Box 3090

Carlsbad, New Mexico 88221

Bryan Howard, Bob Kehrman and Steve Wagner

Westinghouse Electric Company, Waste Isolation Division

P.O. Box 2078

Carlsbad, New Mexico 88221

ABSTRACT

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) faces two major regulatory challenges in its bid to open as the nation's first transuranic (TRU) mixed nuclear waste disposal facility. The first of these major challenges is to demonstrate compliance with the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA's) long-term performance standards of Title 40 Code of Federal Regulations Part 191 (40 CFR 191 Subparts B and C)(1). The 40 CFR 191 disposal regulations limit the amount of radioactive material which is permissible for disposal at WIPP. The U. S. Department of Energy's (DOE's) Carlsbad Area Office (CAO) submitted the Compliance Certification Application (CCA) to the EPA in October 1996. The CCA contains DOE's demonstration of compliance with the performance standards of Part 191. The WIPP cannot open until the EPA certifies that the repository will comply with these standards based on the information provided by the DOE in the CCA. After the submittal date, the EPA began a rigorous and detailed application review process. The EPA issued a proposed rulemaking on October 30, 1997 in which the EPA stated its intent to certify that WIPP will comply with the requirements of Part 191 (2).

The second major regulatory challenge before WIPP is to obtain a hazardous waste operating permit from the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED). The NMED has been granted authority by EPA to implement the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) program in the state of New Mexico. Since a significant fraction of the TRU waste planned for disposal at WIPP is also contaminated with RCRA regulated chemical constituents, a RCRA permit is required to dispose of these "mixed" or co-contaminated wastes.

The DOE initiated work on an application to demonstrate compliance with the EPA's 40 CFR 191 disposal standard in 1993. A draft application was completed in March of 1995, followed by phased submittal of individual chapters in April through August of 1996, and the final application to EPA in October 1997. During the course of the EPA's review of the CCA, a number of issues and comments concerning the application have been raised. Most of these issues were resolved by the DOE with supplemental information submitted for the purpose of clarification. In other instances, complex technical work was conducted by the DOE to verify that the application was accurate, while moving the review process forward in a timely and meaningful way. The CAO successfully answered every challenge offered during the course of the CCA review with timely responses that withstood the tests of technical and scientific soundness.

The DOE initiated work on acquiring a RCRA permit for WIPP in 1990. The RCRA permitting process has been complicated by a number of extenuating factors such as programmatic changes at WIPP, new legislation that changes the responsibilities of WIPP regulators, and influence of stakeholders and members of the public. The DOE has consistently supported moving the NMED permitting process forward. Although, the schedule for granting a RCRA permit has experienced a number of setbacks, the DOE hopes that a final permit will be issued in 1998.

The timely opening of the WIPP facility is a national priority. Proving the safety of WIPP through the use of sound technical and scientific data is a DOE priority. The scheduled opening date of May 1998 is being closely monitored by the Secretary of Energy and Congress to assure the timely, safe isolation of TRU waste from the public and the environment.

Processing and final preparation of this paper were performed by Westinghouse Electric Company's Waste Isolation Division, the management and operating contractor at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, under U.S. Department of Energy contract number DE-AC04-86AL31950.

INTRODUCTION

The U. S. Department of Energy's CAO remains on schedule to open the WIPP facility in May 1998. The WIPP is a deep geologic repository designed and constructed to demonstrate the safe disposal of TRU waste generated by United States defense activities. The CAO has been successful in remaining on schedule for a WIPP disposal decision in 1998, due to the organization's focus and its clear mission. Other keys to this success include early and frequent interactions with the regulators, stakeholders, and members of the public, as well as long-standing support from the public, businesses, and local government of southeastern New Mexico.

As part of the DOE's effort to open WIPP, the DOE must demonstrate compliance with the EPA regulations governing disposal of TRU radioactive waste and the NMED regulations 20 NMAC 4.1 (3), which govern disposal of RCRA hazardous waste. Wastes contaminated with both TRU and hazardous constituents are called TRU-mixed wastes. WIPP is designed to dispose of both TRU and TRU-mixed wastes.

COMPLIANCE WITH EPA TRU WASTE DISPOSAL REGULATIONS

The WIPP Compliance Certification Application (CCA) was submitted to the EPA on October 29, 1996 (4). Upon receipt, the EPA began its formal regulatory review process and initiated a 120 day public comment period. The EPA review was to be completed within one year [LWA Section 8(d)(2)(A)] (5). The EPA began the review process with activities designed to assess the completeness of the DOE application. This led to a number of requests for additional information that the EPA needed to move through the review expeditiously and ensure that the ultimate certification decision could be defended by the technical information on record. Stakeholders, through comments submitted to the EPA WIPP docket, also influenced EPA's requests for additional information, strengthening the application. The EPA actually extended the public comment period by accepting public comments through August 1997. The WIPP docket is EPA's official record of comments sent to its Washington, DC office. Copies of all information sent to the docket were made available at WIPP public reading rooms throughout New Mexico. The EPA issued its completeness determination on May 16, 1997 (6). The collaborative effort, between the regulator, the DOE, and the public, is precisely what the U. S. Congress intended when it amended the WIPP Land Withdrawal Act (5).

All technical areas of the application were evaluated by the EPA in great detail during the course of its technical review, which ended on October 28, 1997, upon EPA's issuance of its Proposed Rule for certification of the WIPP. This rule stated EPA's intent to certify that WIPP will comply with the disposal standards of 40 CFR 191. Some of the more challenging and visible aspects of the technical focus areas will be discussed in this paper. The preparatory time and attention that EPA devoted to all of the technical aspects of the CCA expedited the evaluation as the process moved through the public involvement phase of the regulatory process. The DOE is also convinced that there are no plausible technical concerns that could be raised that could pose a challenge to the EPA's final certification decision for the WIPP.

The EPA also focused on ensuring that its decision-making process complies with the requirements for public involvement, which are driven by the Administrative Procedures Act (APA)(7) and the compliance criteria 40 CFR Part 194 (8). The EPA has gone beyond the minimum required for compliance with both the letter and the spirit of the public involvement requirements in the APA. The DOE is convinced that the EPA>s diligence in assuring that no reasonable challenge can be made to the certification decision has also fortified the administrative process against unwarranted challenges.

The following is a list of the typical sequence of events the EPA uses in a rulemaking when certifying other environmental activities under its jurisdiction and a list which outlines the rulemaking process used for WIPP certification.

Typical EPA Rulemaking Process

EPA Rulemaking Process Used for WIPP Certification

The following is a description of the rulemaking process applicable to the WIPP certification process.

Comparison Between the EPA WIPP Rulemaking Process and the Typical Administrative Rulemaking Process

The rulemaking process applicable to WIPP was comprehensive as compared to the typical administrative rulemaking process, for the following reasons:

THE EPA REVIEW PROCESS: AN OVERVIEW AND

HISTORICAL ACCOUNT

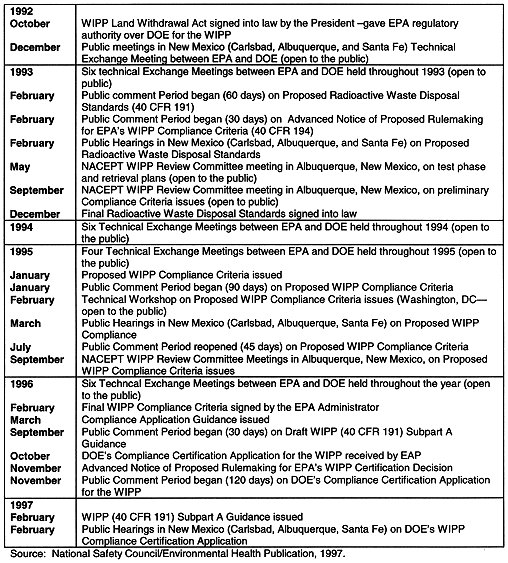

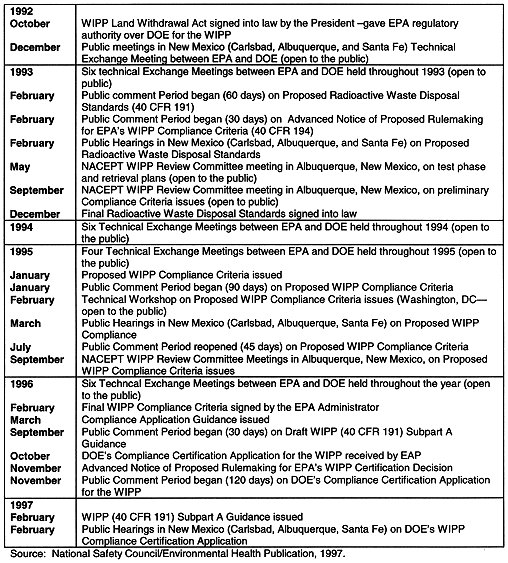

The EPA review process began in October 1996, with the submittal of the CCA. However, the dialogue and communication began much earlier regarding the technical basis that would ultimately support the CCA. The EPA, WIPP oversight groups, and stakeholders have been involved in related technical discussions since 1992, when the last formal WIPP Performance Assessment report (9) was issued (see Table I). The DOE has since issued a series of regulatory documents leading up to issuance of the CCA. This series of regulatory reports has proven to be an extremely valuable forum in which to discuss technical issues. This continuous dialogue with the EPA, project stakeholders, and oversight groups has been critical to the success of the project. Interested stakeholders also voiced their concerns and, therefore, were involved in the DOE decision making. These discussions also allowed the WIPP technical oversight group, the Environmental Evaluation Group (EEG), to fulfill its charter as a WIPP-focused technical oversight group. In addition, these discussions gave the DOE a sound basis from which to demonstrate compliance and allow for the timely opening of WIPP. Table I lists the opportunities that were made available to the public to state their concerns regarding the WIPP application.

Table I. On the Road to the U.S. EPA's WIPP Certification Decision

Early in the review, the EPA focused on the quality assurance (QA) associated with the suite of numerical computer codes used to predict the long-term performance of the WIPP repository. The EPA identified the need for additional QA documentation of the analyses and some computer code users' manuals during this part of the review. The CAO promptly submitted this information to the EPA.

The focus of the EPA review then shifted to the completeness and historical tractability of the information in the PA input parameter data packages. These data packages include information from experimental work conducted from the 1970's to the present. The data packages are detailed, complicated, and quite voluminous. The EPA review activity required much work and resulted in a request to perform a formal expert elicitation for a waste strength-related parameter used in the PA calculations (10). The DOE initiated this work immediately and the recommendations received from the expert panel were reported to the EPA. The expert panel recommendations were included in the EPA Performance Assessment Verification Test which will be discussed in more detail later in this paper.

The EPA focus then moved to issues resulting from peer reviews commissioned by the CAO to support the CCA compliance demonstration. Peer reviews were conducted on the following seven topics.

Three of these peer reviews initially resulted in some unresolved issues. The CAO elected to reconvene panels to resolve open issues. The Conceptual Model Peer Panel had two open issues remaining after their initial deliberations. These two technical concerns were "high visibility" issues and were, consequently, followed closely by the EPA, the EEG, and project stakeholders. The peer panel's remaining concerns were of the CCA spallings model and the assumptions made in the CCA PA relative to MgO backfill (the spallings model is used to predict the amount of material that enters the intrusion borehole as the repository depressurizes, and the role of the MgO backfill is to reduce actinide solubilities by controlling pH levels in the repository). After reconvening the conceptual model peer panel twice (April-June 1996 and March-April 1997), these remaining concerns were resolved (11). The panel concluded that the predicted volumes of spalled materials presented in the WIPP CCA are "reasonable and may overestimate the actual waste volumes that would be released by the spallings process at the WIPP" (11). The peer panel's conclusion was based on additional consideration of processes that could lead to spalled releases.

The EPA review then focused on the CCA PA sensitivity and uncertainty analyses. When an applicant uses computer modeling to characterize risk for the purpose of his compliance demonstration, it is common for the EPA to use a different numerical model designed to model comparable processes, for the purposes of generating results (numerical representations of risk) that can be compared to the risk values reported by the applicant for the purposes of validation. The WIPP PA is a unique and highly specialized suite of numerical codes developed over a number of years for the specific purpose of quantifying probabilistic risk associated with the WIPP repository over a 10,000-year period. Because of this, the EPA elected to use the WIPP PA codes for the purpose of verifying the CCA calculation results. Therefore, the EPA elected to modify some of the input parameters based on their judgment of the associated uncertainty and the relative sensitivity of the CCA PA calculation results. This EPA activity was called the Performance Assessment Verification Test (PAVT). The results of this effort clearly indicated that the repository complied with the 40 CFR 191 release limits in the PAVT exercise. The PAVT, therefore, demonstrated that the CCA PA results are reasonable and appropriate.

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The DOE requested that the Nuclear Energy Agency of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and the International Atomic Energy Agency jointly organize an international peer review of the WIPP PA. The objective of the international review was to examine whether or not the PA was appropriate, technically sound and in conformity with international standards and practices. Overall, the analyses in the CCA were considered to be technically sound. The reviewers noted that the CCA focuses on a demonstration of compliance with the EPA containment requirements based on collective dose considerations. These requirements differ from those based on individual dose and risk used in most countries. However, the CCA presents individual dose estimates for the undisturbed performance of the WIPP based on a conservative hypothetical pathway. In this case, the results indicate that the WIPP meets typical international performance criteria. The reviewers asked for further information, not included in the CCA, on individual radiation doses that might be received as a result of drilling of a borehole into the repository. The results provided by the DOE indicated that, for this scenario, the WIPP facility would also meet standards typical of those used internationally.

Transuranic wastes are currently held in storage at a wide range of facilities around the world. Deep geological disposal is the internationally favored option for safeguarding future generations from the increasing risks of radioactive wastes that are currently stored in deteriorating surface storage facilities. Many countries are presently researching potential deep geologic disposal sites. The WIPP, however, is a landmark in radioactive waste disposal: it is the first deep disposal site both for which an application has been prepared to meet regulatory requirements, and for which certification to the regulatory requirements has been proposed. The probabilistic risk assessment (PRA) used at WIPP is an internationally recognized method similar to those employed in other countries. DOE contractors have contributed substantially to the development of probabilistic methods in the field of repository performance assessment. The arrival at a certification decision through the use of a robust performance assessment and open and iterative technical dialogue will encourage other programs currently involved in site selection and public consultation.

THE RCRA REGULATIONS

The RCRA regulations govern the management of hazardous materials and waste. Typical hazardous waste includes metals such as lead, silver, cadmium, chromium, arsenic, and spent solvents. With the exception of lead, all hazardous waste intended for disposal at WIPP are generally present only in trace quantities. When Congress enacted the RCRA in 1976 (12) it envisioned a regulatory system that would result in sound environmental management of hazardous waste from the moment of their creation to the point when they were either destroyed or were disposed at facilities that met stringent technical criteria. Codification of this approach for hazardous waste began in 1980 (13) when the EPA first issued RCRA regulations. The end result is a complex series of regulatory standards that cover all aspects of the management of hazardous waste and that fill over 1,000 pages in the Code of Federal Regulations.

The state of New Mexico made the necessary demonstrations under RCRA and was authorized on January 25, 1985 (14) to administer the hazardous waste program. Accordingly, the NMED has implemented a hazardous waste management program that is fundamentally the same as the federal program. Within this authorization is the responsibility to regulate the hazardous waste components of mixed waste. There are currently two DOE facilities within New Mexico that have mixed waste facilities that are permitted by the NMED: Los Alamos National Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratory.

The RCRA regulations are built around wastes and waste types the EPA has determined to be harmful to human health and the environment. The wastes include chemicals that are no longer useable for their chemical properties and which are considered by the EPA to be toxic to human health or the environment or wastes which exhibit the characteristic of toxicity, corrosivity, ignitability, or reactivity.

The RCRA regulations embody a series of general facility technical standards that must be met for all waste management facilities. These address topics such as waste characterization, security, training, emergency planning, and inspections. Management facilities addressed in the regulations include containers, tanks, surface impoundments, piles, land treatment units, landfills, incinerators, containment buildings, or corrective action management units. In addition to the general facility technical performance standards, the RCRA also defines technical performance standards for the placement of hazardous waste in each of these standard types of units. Technical performance standards are prescribed actions that an owner/operator of a facility must take in order to assure compliance with the regulations.

In 1987 the EPA realized that not all hazardous waste management units fit the description of the standard units that were initially targeted by the regulations. To accommodate a broader spectrum of waste management units and new technologies, the EPA issued standards for miscellaneous units which are defined as those units that are not containers, tanks, surface impoundments, piles, land treatment units, landfills, incinerators, boilers, industrial furnace, underground injection well, containment buildings, corrective action management units, or a unit eligible for a research, development and demonstration permit. Miscellaneous units include, among other types, mined geologic repositories like the WIPP. Because miscellaneous units could be diverse, the EPA was not able to derive a single set of technical performance standards that would fit all possibilities. Instead the EPA depended on a combination of existing technical standards and environmental performance standards. Technical standards provide protection by meeting certain specific design, construction, and operation objectives. Environmental protection standards goals are to protect human health and the environment from releases along air, surface water, soil, or groundwater pathways.

The EPA intends for the miscellaneous unit standards to be negotiated by the applicant and the regulator. Accordingly, the EPA did not specifically define what constituted adequate protection under the miscellaneous unit rules. They did intend, however, that the applicant would perform pathway analysis as a means of demonstrating the level of protection afforded by the miscellaneous unit and its operation.

THE RCRA PERMITTING PROCESS

The tasks for successful completion of the RCRA process include, preparing and submitting the permit application, followed by a determination of administrative completeness, a technical review, issuance of notice of deficiency (NOD), followed with submittal of information addressing the NOD, determination of technical completeness, issuance of the draft permit, public comment and hearings on the draft permit, and issuance of a final permit. The basis for any successful permitting process is the application. Applications must be complete and accurate. There are no set guidelines for the format and content of an application except for the regulation itself. Title 40 CFR Part 270 (15) details the minimum content of a permit application.

One approach to ensuring the completeness of the application is to obtain a copy of the completeness checklist that regulators use to review the application. All the RCRA regulations should be addressed in the application, even if some are not applicable. Regulatory agencies also have "model permits" to be used as guides for preparing facility specific permits (16,17). These model permits contain all the required elements of a permit plus direction for including facility-specific information such as waste lists, monitoring conditions, and time tables and milestones regarding operations and closure.

Usually, the Technical Review results in a NOD. This covers areas where the regulator determines that there was insufficient technical information provided. Applicants have 30 days to provide any additional information in response to the NOD. Once the regulatory agency is satisfied that it has all needed technical information, it will issue a declaration of Technical Completeness. Subsequently, preparation of the Draft Permit begins. It is at this stage that further changes to the application are discouraged unless specifically requested by the regulator to modify, clarify, or supplement the existing text. After the draft permit is complete, the Public Comment period begins. EPA recently expanded the role of the public in the permitting process by modifying the permitting procedures to provide earlier public involvement, to provide greater public access to information and to provide more opportunities for involvement (18). The final action is the issuance of the Final Permit. Regulatory agencies are required to consider all comments of the applicant, other government agencies, and the public in their final deliberations. Once issued, facilities are subject to inspection and enforcement of the conditions in the permit. Periodically, modifications to the permit are necessary, either at the request of the facility or the regulator. Title 40 CFR 270.42 covers the permit modification process. Permits have fixed durations, generally up to 10 years. Applicants must re-apply at least 180 days prior to the expiration of a permit in order to continue operations past the permit expiration date.

There are no time limits in the federal regulations as to how long the permitting process should take. Historically, treatment, storage, and disposal facility initial permits have taken on the order of two to three years. The regulations, on the other hand, do stipulate time periods for processing applications for permit modifications under most conditions.

THE WIPP RCRA PERMIT PROCESS

The permitting process for TRU mixed waste at the WIPP began with the authorization of New Mexico to administer the RCRA program for mixed waste. This authorization took effect on July 25, 1990 (19). One month later the state of New Mexico specified the due dates for both Part A and Part B of the application. Both were submitted on time in January and February of 1991. The Part A is a standardized form used by regulators to obtain basic information about facilities. The initial Part B was about 5,000 pages in length. During the period following the submittal in early 1991, the DOE and the NMED had several meetings to discuss the content of the application and to define what information was needed in order to proceed with a timely review. The NMED requested detailed information on the design of the facility, the geology, the waste and plans to characterize it, and plans to close the facility.

Over the two year period between February 1991 and January 1993, the application grew to about 60,000 pages. Because the WIPP mission at this time was to conduct tests in the underground and then retrieve the waste, the amount of modeling needed was minimal to demonstrate protection of human health and the environment as the result of operations in the miscellaneous unit.

The NMED proceeded to the point of issuing a draft permit before the DOE altered its course regarding the use of WIPP for testing and decided to proceed with permitting the facility for disposal beginning sometime in 1998. This redirected permitting activity began when the NMED Secretary sent the draft permit back to the Department's Hazardous and Radioactive Materials Bureau directing them to obtain a revised permit application from the DOE. That revised application was submitted in May 1995 after nine months of discussions with the NMED and several public forums to obtain input from stakeholders. The May 1995 submittal, which requested a permit for disposal operations, included extensive numerical modeling of air emissions to demonstrate protection of human health and the environment. The application presented evidence that there would be no-migration along other pathways.

Since submittal of the revised application, the DOE has been working to provide the NMED with all the information it needs to prepare the draft disposal facility permit. On several occasions, the NMED sought additional information to supplement, clarify, or modify the existing text in the application. In January 1998, the NMED declared the application to be technically complete. After the NMED drafts the permit, the public comment and hearing process will follow. After this process is completed and all related issues are resolved, a final permit may be issued and WIPP will be allowed to dispose of mixed waste.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE REGULATORY DECISIONS

SIMILAR IN NATURE

The EPA certification decision for WIPP will set an example for similar nuclear waste management decisions in the U. S. and in other countries. Many national and international programs of these will now move forward using the EPA's process as a model. It is recognized that there are those who favor a safety assessment in lieu of PRA tools for such decision making processes. This international debate may continue because each of these approaches has its strengths and weaknesses. There is a global use for each in the future depending upon the needs and the political framework within which these decisions are to be made. Similarly, the NMED permitting process under RCRA will provide an example for permitting a unique facility. Because the RCRA regulations are administered by most states in the U. S., but not all, the RCRA process for WIPP will have many commonalties for future waste repositories.

SUMMARY

The EPA was diligent and focused during the course of the CCA review process. Technical detail was a priority, as well as moving the process forward in a meaningful way with systematic expedience. It is unlikely that any challenge to an EPA decision to certify WIPP, from either a technical or procedural perspective, will be successful. It is unclear when WIPP will receive a RCRA permit from NMED. Obtaining a RCRA permit for a complex and controversial facility is possible, although it can be a long and arduous process. Providing a complete application, developing an honest and frank relationship with the regulator, and maintaining an openness to the public can be instrumental in keeping the permitting process moving forward. The NMED continues to work on the WIPP permit and the DOE hopes a final permit will be issued in 1998. The fact that a RCRA permit receipt date cannot be predicted with any certainty has motivated DOE to consider its options with respect to receipt of waste in May 1998. DOE may legally ship TRU waste to WIPP that is not contaminated by RCRA constituents. When the NMED issues a RCRA operating permit for WIPP, the CAO can begin shipment of mixed TRU waste. Ultimately then, the CAO can move forward with WIPP in a timely way, while remaining in compliance with applicable requirements.

REFERENCES

1. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "40 CFR Part 191 Environmental Radiation Protection Standards for the Management and Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel, High-Level and Transuranic Radioactive Wastes: Final Rule," Federal Register, Vol. 58, No. 242, pp. 66398-66416, Office of Radiation and Indoor Air, (December 10, 1993).

2. Federal Register Proposed Rule, Pages 28792-288838, Volume 62, No. 210, Thursday, October 30, 1997.

3. New Mexico Administrative Code, Title 20, Chapter 4, Part 1, November 1, 1995.

4. U.S. Department of Energy, "Title 40 CFR Part 191 Compliance Certification Application for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant," DOE/CAO-96-2184 (October, 1996).

5. U.S. CONGRESS, "Waste Isolation Pilot Plant Land Withdrawal Act," Public Law 102-579, 106 Stat. 4777, October 1992. 102nd Congress, Washington, D.C. as amended by the National Defense Authorization Act for the Fiscal Year 1997, Public Law: 104-201 (September 23, 1996).

6. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, letter from C. M. Browner of the EPA to F. Pena, Secretary of the DOE, declaring the CCA complete, Office of Radiation and Indoor Air (May 16, 1997).

7. United States Title Code 5 ' 500 Administrative Procedure.

8. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "40 CFR Part 194: Criteria for the Certification and Re-Certification of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant's Compliance with the 40 CFR Part 191 Disposal Regulations, Final Rule," Federal Register, Vol. 61, No. 28, pp. 5224-5245, Office of Radiation and Indoor Air, (February 9, 1996).

9. PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT DIVISION, "Preliminary Performance for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant," December 1992. SAND 92-0700, Volumes 1-5. Sandia National Laboratories, WIPP, Albuquerque, NM (1992).

10. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Letter from E. R. Trovato, Director of ORIA, to G. Dials, Manager CAO, Identifying parameters for the PAVT, Office of Radiation and Indoor Air (April 25, 1997).

11. U.S. Department of Energy, "Conceptual Models Third Supplementary Peer Review," (April, 1997).

12. U. S. Congress, 1976, "Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (Solid Waste Disposal Act)," 42 U.S.C. '6901 et seq., Public Law 94-580, Oct. 21, 1976, Washington, D.C.

13. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1980, "Identification and Listing of Hazardous Waste," 45 FR 33119, May 19, 1980, Washington, D.C.

14. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1985, "State of New Mexico: Final Authorization of State Hazardous Waste Program," 50 FR 1515, Jan. 25, 1985, Washington, D.C.

15. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1983, "EPA Administered permit Programs: The Hazardous Waste Permit Program," 40 CFR Part 270, April 1, 1998 as revised, Washington, D.C.

16. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1988, "Model RCRA Permit for Hazardous Waste Management Facilities (Draft)," EPA/530-SW-90-049, September 1988, Washington, D.C.

17. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1992, "Model Permit for RCRA Subpart X Units that Treat Energetics," Draft Guidance, April 1992, Washington, D.C.

18. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 196, "RCRA Expanded Public Participation rule," EPA 530-F-95-030, February 1996.

19. U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1990, "State of New Mexico: Final Authorization of State Hazardous Waste Program," 55 FR 28397, July 11, 1990, Washington, D.C.