NEZ PERCE TRIBE’S TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND

PERSPECTIVES ON THE LAND USE PLAN FOR

THE HANFORD SITE

S. M. Sobczyk, R. O. Cruz, and K. L. Baptiste

Nez Perce Tribe

Department of Environmental Restoration and Waste Management

ABSTRACT

The land use plan for the Hanford Site represents the vision of the Nez Perce Tribe Department of Environmental Restoration and Waste Management (ERWM) for the management of the Hanford Site and preservation of the natural and cultural resources at Hanford. The Nez Perce have always considered that the land and its creatures are essential to everyday life. Humans are considered to be only one small part of a much larger circle of life on earth. The earth, in Nez Perce’s belief, is the ever nourishing mother, as any mother provides for a child. These values are used in developing the land use plan for the Hanford Site.

ERWM envisions preservation as the prdominate future land use for the Hanford Site. The entire North Slope would be designated for preservation. The Columbia River would be designated for low-intensity recreation. The islands would be designated as preservation and provides additional protection to sensitive cultural areas, wetlands, and sensitive species. The B Reactor area would be converted into a museum and related facilities. The K Reactor Area could be used for fish farming and aquatic research. The remainder of land within the Reactor Areas would be designated for preservation. Lands within the Central Plateau geographic study area would continue to be used for the management of radioactive and hazardous waste. Our land use plan sets aside ample land for economic development. It includes lands for future development by the City of Richland (City of Richland’s Interim Urban Growth Area) at the southeast portion of the Site. The Fitzner/Eberhardt Arid Lands Ecology Reserve area and viewsheds for Native American vision sites, such as Gable Butte and Gable Mountain, would be protected by a preservation land use designation.

INTRODUCTION

The Nez Perce Tribe’s Department of Environmental Restoration and Waste Management (ERWM) has prepared a land use plan for the Revised Draft Hanford Remedial Action Environmental Impact Statement and Comprehensive Land Use Plan (HRA-EIS) to evaluate the potential environmental impacts associated with future uses of the Hanford Site over the next 50 years. Working with state and Federal agencies, Tribal Nations, and other key stakeholders, ERWM evaluated several alternative land use plans, which included analyzing and the potential environmental consequences associated with each alternative plan. Our land use plan identifies current assets and resources related to land-use planning and provides analysis of and recommendations for future land uses and accompanying restrictions at the Hanford Site over a 50-year period.

The Hanford Site occupies 1,450 km2 (560 mi2) in the southeastern portion of the State of Washington. Established by the Federal government in 1943, the Hanford Site is owned by the Federal government and operated by the U.S. Department of Energy, Richland Operations Office (DOE-RL).

The Hanford Site, including the Columbia River, has a history since time immemorial as a gathering place for Indian nations to hunt, fish, trade and feast. The Nez Perce have shared and participated in these known ancient and traditional activities with other tribes where there were no fences, boundary lines or treaties. The Hanford Site is one of the largest areas of land in the region that has not been developed, with agriculture being the principal development on surrounding lands. The Hanford Site contains the last unimpounded stretch of the Columbia River in the United States, and the Hanford Reach is the only remaining area on the Columbia River where Chinook salmon still spawn naturally. The Fitzner/Eberhardt Arid Lands Ecology (ALE) Reserve contains one of the few resident elk herds in the world that inhabits an arid area and one of the largest remnants of relatively undisturbed shrub-steppe ecosystem in the State of Washington. There are about fifty species of animals that are classified as sensitive species residing at the Hanford Site. The largest populations of sage sparrows in the Washington State can also be found at Hanford. The vision for the Hanford Site would protect these resources while supporting future DOE missions and future economic development of the Tri-Cities as well as the surrounding counties.

Nez Perce ERWM’s Vision for the Hanford Site

Figure 1 presents the vision of ERWM for the management of the Hanford Site and preservation of the natural and cultural resources at Hanford. Protection of cultural resources at the Hanford Site is our utmost priority. Sharing the knowledge and point of view of the Nez Perce Tribe to the non-native about sacred sites and nature is vitally important. Cultural resources remain important to the Nez Perce Tribe’s way of life and are part of the Tribe’s tradition.

Figure 1. Hanford Site Proposed Land Use Plan

ASSUMPTIONS REGARDING FUTURE USE

The assumptions used to develop Figure 1 are as follows:

PLANNING GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND VALUES

The Nez Perce have always considered that the land and its creatures are essential to everyday life. Humans are considered to be only one small part of a much larger circle of life on earth. Nez Perce stories exemplify this intimate relationship between humans and the earth. Traditional Nez Perce culture weaves an intimate relationship between humanity and nature. In all phases of their daily lives, the Nez Perce recognize the spirits of the forces and objects around them as supernatural guardian forms which they call in a personal way their Wyakin. The Nez Perce identify themselves with all the natural features of the earth. The earth, in Nez Perce’s belief, is the ever nourishing mother, as any mother provides for a child. We must continue as caretakers of the earth, or life will surely end soon. These values are used in developing our landuse plan.

APPLICATION OF THE LAND-USE DESIGNATIONS TO THE SITE

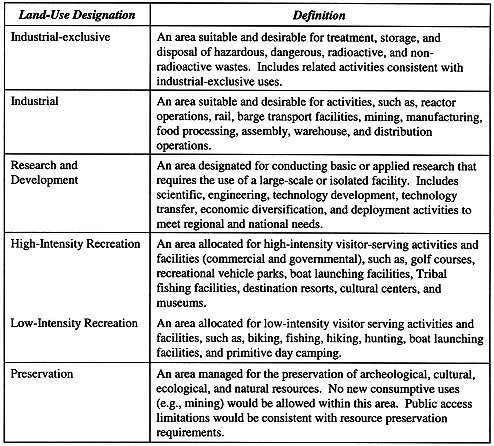

Definitions of individual land-use designations were developed by the cooperating and consultancy agencies so that alternative land-use plans could be developed and compared. The generic land use designations determined to be suitable for the Hanford Site lands included (1) industrial, (2) agricultural, (3) research and development, (4) recreational, (5) conservation with mining and grazing allowed, (6) conservation with mining allowed, and (7) preservation. However, realizing that there were varying degrees of both industrial and recreational use, the cooperating and consultancy agencies decided to split industrial and recreational into two categories—exclusive and unrestricted for industrial and high-intensity and low-intensity for recreational. Once consensus was reached on the land use designations, definitions for these designations were developed. The Hanford Site land use designations and their definitions, which used by ERWM, are presented in Table 1.

Table I. Hanford Site Land-Use Designations

The location, shape, and size of the land-use designations were influenced by a thorough analysis of the existing cultural resources, man-made hazards and resources, and geology.

North Slope

The entire North Slope would be designated for preservation which requires slight changes in current management practices. Our plan would place the North Slope in preservation land-use status for the following reasons:

Figure 2. Hanford Site Topographic Constraints to Land Use

A series of bluffs occurs for a distance of approximately 35 miles along the eastern and northern shores of the Columbia River. In the northern portion of the area, these bluffs are know as the White Bluffs. A study of the Hanford Reach, by USGS geologists (Hays and Schuster, 1986) concluded that nearby irrigation has accelerated the rate of landslides occurring in the area.

The bluffs consist predominantly of sediment know as the Ringold Formation (Lindsey, 1996). These sediments were deposited between six and 3.5 million years ago in a depression referred to as a basin (Fecht and others, 1987). This basin has been named the Pasco Basin, and it is bounded by the Saddle Mountains to the north, Rattlesnake Hills to the southwest, and the Palouse slope on the east (DOE, 1988).

Hays and Schuster (1987) conclude that the entire area of the Bluffs along the northern and eastern shores of the Columbia River are susceptible to landslides. Currently, there are four areas of recent landslides. Moving from upstream to downstream, there are the Locke Island, Savage Island, Homestead Island, and Johnson Island slide areas. The length of these slides parallel to the river shoreline ranges from more than a mile at Locke Island to about one-quarter of a mile near Homestead Island. The Hanford powerline area shows evidence of Late Pleistocene landslides and the area coincides with lack of irrigation adjacent to the bluffs (Hays and Schuster, 1987). The landslides, both active and inactive, total about 4.3 square miles in area, and the total landslide susceptible area is about 5.8 square miles (Hays and Schuster, 1987). These slide areas are characterized by major cracks about two-thirds of the way up the bluff face, surface areas on the slopes below the cracks with a jumbled chaotic ground surface, and mud flows at the base of the slope. The irregular surface forms as the bluff face slides away and begins to break up. The mud flows occur as a result of a process known as liquefaction, that is water saturated soil flowing similar to a liquid. Some of the slide areas, such as Savage Island and Locke Island slides, are rimmed by a scarp or cliff. Surface cracks located upland of the bluff face can be found. These cracks indicate the slopes behind the bluffs are very unstable and prone to future landslides.

Examination of slide areas reveals the universal presence of water seeping from the Bluffs in springs and marshes. There can be little doubt that water is the primary cause for these landslides as verified by the observation of springs, saturated cliff faces, and mud flows. The water found in the Bluffs reduces the strength, decreases frictional resistance, and adds weight to the unconsolidated Ringold Formation. Because the transmissivity of the Ringold layers varies, water will accumulate in certain sediment layers within the Bluffs. This wet layer is the plane upon which the slide begins. The bluff above a wet layer will slide when the water laden and lubricated layer fails under the weight of the overburden.

Sources of water on the Bluffs are natural precipitation, irrigated farmlands, irrigation and waste water canals, and irrigation waste water ponds located up slope east of the Bluffs and on the North Slope. Water from these activities percolates through the soil to the Ringold Formation. Some of these layers resist the downward flow of water, forcing it to flow laterally. Since Ringold layers dip toward the Columbia River, water that collects above less tranmissive Ringold layers will move down slope toward the Bluffs. Eventually this water will reach the Bluffs and becomes the source of water triggering the landslides. Hays and Schuster, 1987 concluded "In the present climate, most of these bluffs are very stable under natural conditions, but irrigation of the upland surface to the east, which began in the 1950’s and has been greatly expanded, led to increased and more widespread seepage in the bluffs and to a spectacular increase in slope failures since 1970. With continuing irrigation, areas of the bluff wetted by seepage will be subject to landslides wherever slopes exceed about 15 degrees and , on lesser slopes, wherever the surficial material is old landslide debris."

The hazards posed by landslides in bluffs ranges from minor to catastrophic. Economic loss from landslides in the Bluffs has not been large because the area is relatively undeveloped. Road closures have occurred. A concrete flume, part of the Ringold Wasteway, was destroyed by the Homestead Island slide in the late 1960’s (Hays and Schuster, 1987). Encroachment up slope by the Savage Island slide destroyed the river-ward margins of irrigated fields along the top of the bluffs (Hay and Schuster, 1987). The Locke Island slide has caused the loss of cultural artifacts on Locke Island by changing the channel of the river and causing erosion to occur on Locke Island. Since its beginning in the mid 1970’s, the Locke Island slide has extended 150 meters into a channel of the Columbia River (Nickens and others, 1997). Since November 1995, transects on Locke Island show an actively eroding cut bank that is 400 meters in length and a horizontal loss of 16 meters (Nickens and others, 1997). Additionally, slides such as this disturb and destroy salmon spawning beds by siltation. An increase in sediment load in the Hanford Reach may adversely affect the Washington Public Power Supply System Reactor cooling-water intake systems (Hays and Schuster, 1987).

The U.S. Government operation of eight "single-pass" (open-coolant) reactors along the Columbia River from 1944 to 1971 at the Hanford Site requires protection for the Hanford Reach. During this time period, the Hanford Site released more than 100 million curies of radioactivity into the Columbia River and tons of toxic contaminants into the soil column surrounding the reactors. River water, used for cooling, flowed through Hanford’s reactors and back into the Columbia River carrying nuclear fission products. Additionally, fuel slug ruptures, chemicals added to the cooling water, and neutron activated particles and debris from reactor purging (cleansing) operations entered the river. Fortunately the overwhelming majority of radionuclides released were short-lived and nearly all of the radioactive material has decayed to harmless levels. The remaining areas of radioactivity are generally located in the slack water areas of the Hanford Reach such as the sloughs and portions of the islands. These areas have been identified by aerial gamma-ray surveys (EG&G, 1990). Riverbed sediments and floodplain soils of the Hanford Reach constitute a sink for many of the pollutants released to the environment by Hanford’s operations. Any shoreline activities which effect the flow of the Columbia River risk the remobilization of contaminants entombed within river sediments.

Perhaps the most unlikely occurrence would be an earthquake triggered, massive slope failure caused by liquefaction of the White Bluffs (Harty, 1979) which would temporally block the Columbia River. Hanford facilities on the west side of the river could be endangered as well as citizens and property located downstream of this temporary dam. Also, contaminants left at depth in the soil column would be further mobilized by the subsequent rise in groundwater levels on the Hanford facilities side of the river.

Columbia River

The Columbia River Corridor would include high-intensity recreation, low-intensity recreation, research and development, and preservation land-use designations. The Columbia River (surface water only) would be designated for low-intensity recreation. The islands would be designated as preservation which would be consistent with current management practices and provides additional protection to sensitive cultural areas, wetlands, and sensitive species. The B Reactor and surrounding area, which is located within the Columbia River Corridor, would be designated for high-intensity recreation and would be converted into a museum and museum related facilities. The B Reactor was the first full-scale nuclear reactor in the world and was critical in the development of the first nuclear weapons. K Reactor Area would be designated as research and development. The K Reactor Area could be used by the tribes and others for fish farming or aqua-culture and aquatic research. The prohibition of further irrigation and other land uses which increase infiltration on both sides of the Hanford Reach will aid in the stabilization of the Columbia River’s shoreline. This measure will protect public health and the environment by preventing remobilization of contaminants entombed within the river’s sediment and the shoreline’s soil column. It will prevent siltation and destruction of salmon spawning beds.

The remainder of land along the river would be designated for preservation. This designation would protect the retained rights of Native American tribes to the area and at the same time would provide protection to sensitive cultural and biological resource areas. Irrigation of the Horn Area would mobilize contaminants left behind at depth in the Reactor Areas long after clean-up efforts have ceased (Figure 3). Since the clean-up efforts in the Reactor Areas soil column is limited to a depth of about 20 feet below ground surface, then contaminants left in the soil column below 20 feet will not be remediated. A similar clean-up strategy has been proposed for the Central Plateau. Contaminants left in place at depth in the soil column after the Hanford Site’s remediation may result in further degradation of the Columbia River. If irrigation of lands on or near the site occurs, the subsequent rise of the water table will remobilize contaminants and provide a pathway for contaminants to reach the Columbia River. The contamination left at depth poses a potential hazard to development. Even facilities associated with low intensity recreation may increase infiltration of natural precipitation. Where vegetation is suppressed and gravel covers are used, i.e. campgrounds, infiltration of precipitation will occur at a higher rate driving contaminants toward groundwater. Shelters over picnic tables will shed water and increase infiltration. Infiltration through the vadose zone in the Reactor Areas is supplying contaminants to groundwater in the Reactor Areas. Travel time within the aquifer from waste sites in the Reactor Areas to the river is relatively short (months). Since reactor operations ceased more than 20 years ago and contaminant levels (i.e. chromium) in groundwater have remained elevated, the source of the present high levels of contaminants is the vadose zone. Any activities which increases the amount of water on the ground surface such as irrigated grass for golf courses increases infiltration. Activities such as grazing will increase infiltration through the removal of vegetation and increase erosion.

Figure 3. Hanford Site Vadose Zone Contamination

A predominately preservation land use designation for the Columbia River Corridor would limit the risk of remobilization of contaminants entombed within river sediments. River water, used for cooling, flowed through Hanford’s reactors and back into the Columbia River carrying nuclear fission products. Additionally, fuel slug ruptures, chemicals added to the cooling water, and neutron activated stellite (cobalt-60) particles and debris from reactor purging (cleansing) operations entered the river. Riverbed sediments and floodplain soils of the Hanford Reach constitute a sink for many of the pollutants released to the environment by Hanford’s operations.

The extent and amount of discrete cobalt-60 particles in the river has never been thoroughly investigated. The actual amount of neutron activated material transported to the Columbia River is not known. The studies done by DOE-RL’s contractors have not been concentrated on those areas of the river system where these particles are predisposed to accumulate. Based on Stokes Law and the physical properties of sand and stellite (Sula, 1980; Cooper and Woodruff, 1993), stellite particles entrained into the river’s bedload have preferentially settled in areas dominated by sand-size grains. EG&G Energy Measurements (1990) presents an aerial gamma-ray survey of the area which is often cited by DOE-RL as indicating that the river corridor is relatively free of radiation hazards. Due to shielding by soil, water, vegetation, and air as well as the motion of the detector, aerial gamma-ray surveys lack the sensitivity and resolution required to aid in the determination of concentration of cobalt-60 particles. The non-random distribution of the cobalt-60 particles into discrete areas and the presence of water within the detector’s ‘field of view’ (Sula, 1980) further reduces the utility of aerial gamma-ray surveys in determining the potential for cobalt-60 particles. The sandy areas of the Hanford Reach have never been thoroughly examined for the presence of radionuclides. For example, the sandy portion of D island "has not received a detailed survey for discrete radioactive particles" (DOE, 1997). The surveys which have been done to date have been randomly placed while the deposition of these cobalt-60 particles by the Columbia River is not a random process. Therefore, determining the concentration of cobalt-60 particles based on a random sampling pattern is strongly biased toward underestimating the actual concentration of cobalt-60 particles in the Columbia River shoreline.

Central Plateau

Lands within the Central Plateau geographic study area would continue to be used for the management of radioactive and hazardous waste materials and would be designated for industrial-exclusive use. These management activities would include collection and disposal of hazardous waste materials that remain on-site, contaminated soil and groundwater containment and clean-up, and other related and compatible uses. Deed restrictions would likely be applied to this area through the CERCLA and RCRA processes. This designation would also allow expansion of existing facilities or development of new waste management facilities as well as facilities for future DOE missions.

All Other Areas

The All Other Areas would include industrial, research and development, and preservation land-use designations. Alternative Two sets aside ample land for economic development. It includes lands for future development by the City of Richland (City of Richland’s Interim Urban Growth Area; Figure 1). Projected federal and nonfederal industrial growth for the next 50 years would be accommodated within the lands identified by the City of Richland Urban Growth Area boundary at the southeast portion of the Site. Existing facilities on the site that could continue are LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory), WPPSS (Washington Public Power Supply System nuclear reactor for electric power generation), and FFTF (fast flux test facility). The FFTF area would also be reserved for future DOE missions. The resident elk herd, one of the largest remnants of relatively undisturbed shrub-steppe ecosystem, and viewsheds for Native American vision sites, such as Gable Butte and Gable Mountain, would be protected by a preservation land use designation.

The major constraints shown on Figures 2 and3 and the safety buffers around the nuclear facilities (FFTF, WPSS, and the Central Plateau) demonstrate that the majority of the Hanford Site is unsuitable for economic development and that the best future land use is preservation. Portions of the All Others Areas have a well developed transportation network; however, these areas are remote from the population centers limiting their economic potential. Soil and groundwater contamination left at depth after remediation prevents these lands from being exploited for economic reasons due to the difficulties involved in transferring public lands with environmental liabilities to private ownership. Extensive economic development of the All Other Areas is also precluded by the large safety buffers around the Hanford Site’s existing nuclear facilities. The nature of the research conducted at LIGO requires a substantial buffer zone for operation.

The promontories of Gable Mountain, Gable Butte, Umtanum Ridge, and a large portion of their viewsheds would be designated for preservation, which would be consistent with traditional tribal use. The Old Indians went to high mountains seeking vision sites and to fast for a few days to seek a vision or a Wyakin (Nez Perce word for your personal vision spirit that will protect you for the rest of your life). The Wyakin could be a bird, four-legged animal, plant, or root, and it will be your personal medicine. During a vision quest, one looks at the big picture or the view as far as the eye can see. This view encompasses the big river, creeks, springs, the various grasses, shrubs, animals, birds, and even insects such as little ants. These things and objects all have their place and souls on the mother earth. One prays to the creator to bless you and ask him to take care of all these things.

The large contiguous tract of shrub-steppe habitat that surrounds the Central Plateau would be designated for preservation. A sand dune complex and vegetation stabilized sand dunes, which extends from the Columbia River westward across the site to Highway 240, is designated preservation since vegetation disturbing activities may reactivate stabilized due fields. Thus, this area is unsuitable for economic development. The preservation land-use designation would ensure that wildlife corridors are maintained.

The Arid Lands Ecology Reserve

The ALE Reserve geographic study area would be designated for preservation with one exception that would allow development of privately owned mineral rights. These mineral rights were not conveyed to the federal government when the Hanford Site was formed. The ALE Reserve would continue to be managed as preservation in accordance with the National Environmental Research Park designation and the USFWS permit. The ALE Reserve contains one of the few resident elk herds in the world that inhabits an arid area and one of the largest remnants of relatively undisturbed shrub-steppe ecosystem in the State of Washington.

CONCLUSIONS

The land use plan for the Hanford Site represents the vision of the Nez Perce Tribe ERWM for the management of the Hanford Site and preservation of the natural and cultural resources at Hanford. The Nez Perce have always considered that the land and its creatures are essential to everyday life. Humans are considered to be only one small part of a much larger circle of life on earth. The earth, in Nez Perce’s belief, is the ever nourishing mother, as any mother provides for a child. These values are used in developing the land use plan for the Hanford Site.

ERWM envisions preservation as the prdominate future land use for the Hanford Site. The entire North Slope would be designated for preservation. The Columbia River would be designated for low-intensity recreation. The islands would be designated as preservation and provides additional protection to sensitive cultural areas, wetlands, and sensitive species. The B Reactor area would be converted into a museum and related facilities. The K Reactor Area could be used for fish farming and aquatic research. The remainder of land within the Reactor Areas would be designated for preservation. Lands within the Central Plateau geographic study area would continue to be used for the management of radioactive and hazardous waste. Our land use plan sets aside ample land for economic development. It includes lands for future development by the City of Richland (City of Richland’s Interim Urban Growth Area) at the southeast portion of the Site. The ALE Reserve area and viewsheds for Native American vision sites, such as Gable Butte and Gable Mountain, would be protected by a preservation land use designation.

REFERENCES