IS DISPOSAL OF DOE LLW AT COMMERCIAL SITES

REALLY MORE COST EFFECTIVE?

Lee Sygitowicz, Kevin Van Cleve, and Carlos Ramirez

Bechtel Nevada

Russell Barber, P.E., Ph.D.

Bechtel National, Inc.

ABSTRACT

As a result of ever-tightening budget constraints, some sectors of government have begun to use business strategies developed in the marketplace to improve their services and reduce costs. Although the government is not allowed to compete with private business, some overlap of services is being provided by both groups. This gives the federal customer alternatives for needed services and fosters an atmosphere of pseudo-competitiveness among the service providers. One example of this is disposal services for U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) low-level radioactive waste (LLW). With the development of new commercial LLW disposal sites, LLW generators have alternatives to using existing DOE sites or constructing onsite facilities. With an increasing amount of DOE LLW being shipped to commercial disposal facilities, DOE disposal facilities, such as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) and Hanford, have experienced an increase in the per-unit rate charged for disposal services. This is the result of waste volumes smaller than are needed to offset operating costs because these facilities operate on a cost recovery basis (no profit is involved). Since 1994, DOE has sent more than 1.6 million cubic feet of LLW to Envirocare of Utah, Inc. at a disposal fee of $7 to $10 per cubic foot, and several million cubic feet more is currently scheduled for disposal at Envirocare over the next 5 years. A cursory analysis would suggest that disposal at Envirocare results in a cost savings of about 33 percent when compared to disposal at NTS because of the lower disposal fees and the availability of less expensive rail transportation to the Envirocare site. However, a more careful analysis shows that DOE's own waste disposal operations have the capacity to handle considerably more LLW volume at little or no increase in disposal operating costs. Our analysis shows that by sending an increased volume of LLW to its own disposal facilities, DOE could save more than $30 million over the next 10 years.

BACKGROUND

U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Order 5820.2a currently requires that "DOE-low-level waste shall be disposed of on the site at which it is generated, if practical, or if on-site disposal capability is not available, at another DOE disposal facility." In 1993, a DOE Assistant Secretary approved authorization to all field office managers for commercial disposal of small quantities of "radioactive mixed waste" if the field office obtained approval from EM-30 for exemption from the order before actual disposal of the waste. Small quantities are defined as less than 1,000 cubic yards of waste per year per program or installation. In 1992, several concerns were raised regarding the use of commercial disposal facilities. Specific conditions were defined that needed to be met before an exemption for use of commercial disposal would be granted. In 1993, another DOE Assistant Secretary approved the use of commercial disposal of radioactive waste by granting an exemption from the order for environmental restoration activities at certain locations or facilities not located at major DOE installations. He also delegated authority to Operations Office managers to grant case-by-case approvals for exemptions from the order to allow for the commercial disposal of small quantities of mixed waste.

Currently, DOE has six operating disposal sites for low-level waste (LLW) and mixed low-level waste (MLLW). It also has restrictions related to the location of disposal based on the defense or non-defense origin of the waste. The Nevada Test Site (NTS) is designated as the preferred DOE site for disposal of defense-related LLW, and Hanford is designated for disposal of non-defense-related LLW. In September 1996, a DOE disposal work group issued draft recommendations for the future configuration of DOE facilities for disposal of MLLW and LLW. Therecommendations were to use commercial disposal sites extensively for lower activity waste and reduce the number of DOE disposal sites from six to three (NTS, Hanford, and the Savannah River Site). NTS would be the lead DOE site for LLW disposal, while the Hanford site would provide surge capacity, and Savannah River would provide regional use. Hanford would be the lead DOE site for MLLW disposal, with NTS as a backup to provide surge capacity. The work group pointed out the need to maintain a strong DOE disposal capacity rather than relying solely on commercial capacity because commercial facilities can receive only low-activity waste (Class A). The work group recommendations would eliminate defense-related origin as a criterion for disposal location. These recommendations are currently under consideration.

Chapter IV of DOE Order 5820.2a states that only "small volumes of DOE waste containing 11e(2) byproduct material . . . may be managed as low level waste" at DOE sites. This directive was intended to apply to cleanup of uranium mill tailings 11e(2) material, which was a part of the DOE Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) program. However, the current wording is being interpreted to apply to all 11e(2) materials, including material that is not part of the UMTRA program, such as some waste from the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program.

Several sites have been exempted from DOE Order 5820.2a and have been allowed to ship waste to commercial disposal sites because of perceived lower costs. DOE-Headquarters (DOE-HQ) is currently considering giving a blanket exemption to 5820.2a that would allow any DOE site to ship LLW to commercial facilities. The basis for the proposed exemption is primarily that commercial disposal of Class A LLW is apparently less expensive. Based solely on a comparison of current commercial and DOE site disposal fees, this appears to be true. However, a different approach to disposal at DOE sites could result in savings of millions of dollars for DOE.

PROBLEM

Currently, increasing amounts of DOE LLW are being shipped to commercial disposal facilities rather than to DOE disposal facilities. Since 1994, DOE sites have sent more than 1.6 million cubic feet of LLW to Envirocare of Utah, Inc. at a disposal fee of $7 to $10 per cubic foot. Several million cubic feet of DOE waste is scheduled for disposal at Envirocare over the next 5 years. Low disposal fees, accessibility by rail, and the ability to dispose of bulk waste make Envirocare and other commercial disposal sites attractive alternatives to disposal at NTS or Hanford. This has resulted in a projected decline in the volume of waste sent to NTS and a corresponding projected increase in the NTS disposal fee.

Table I summarizes cost comparisons for disposal fees and cross-country shipping for waste disposal at NTS and the Envirocare facility in Utah. Disposal fees at NTS for FY 1997 ranged from $7.75 to $17 per cubic foot. These rates were based on the estimated waste volume of 850,000 cubic feet for fiscal year 1997 and a loaded baseline waste management cost of $6.2 million. The disposal fees also covered supplemental costs for special projects tasks, for a total cost of $8.069 million. This equals an average disposal cost of $9.49 per cubic foot, a unit rate considerably higher than the $6.38 to $8.70 disposal fee available at Envirocare. A first look, then, suggests that $1.37 per cubic foot can be saved by using commercial LLW disposal.

Table I. Waste Disposal Fee and Cross-Country Shipping Costs

An additional key factor that directly affects the cost to the generator for disposing of LLW at NTS is the lack of rail access to the site. This is particularly important for transporting soil-like wastes that can be shipped in gondola rail cars. For example, bulk materials in gondola rail cars can be shipped from Ohio to NTS for $76 per ton or $3.38 per cubic foot. The cost for shipping the same material by truck is about $117 per ton or $5.20 per cubic foot. This represents a cost saving of $1.82 per cubic foot for shipping the material by gondola rail cars compared to shipping it by truck.

The combination of the lower disposal fee and less expensive cross-country transportation reduces costs by $3.19per cubic foot, a 33 percent savings. This suggests that as much waste as possible should be shipped to Envirocare rather than NTS. However, because Envirocare can accept only Class A waste, higher activity and classified waste must be shipped to NTS for disposal. Such waste requires deeper burial and more frequent covering, factors that increase costs and create inefficiencies in NTS disposal operations. Ultimately, if an increasing percentage of Class A LLW is shipped to commercial facilities, while the LLW shipped to NTS is primarily Class B and C waste, the fee for waste disposal at NTS will become very high. This situation is similar to the problems encountered by the waste compacts, where if generators procure disposal services outside the compact, the per-unit cost for the remaining generators goes up because the service provider must cover operational costs to remain solvent. Therefore, it is essential that, for NTS to remain a viable disposal site for the foreseeable future, an adequate volume of Class A waste must be shipped there.

NTS waste management personnel are actively pursuing ways to reduce disposal costs at NTS by increasing efficiencies through the use of practices from the private sector. The obvious means of increasing efficiency is to reduce down or non-productive time and fully use available resources by increasing the yearly volume of waste disposed of at NTS and maintaining a firm shipping and receiving schedule. These changes would result in a lower per-unit disposal fee and overall savings to the government. However, there are some impediments to increasing the waste volume being sent to NTS, including the higher disposal fees and transportation costs. Table II summarizes these impediments and lists possible ways of removing them. Actions to implement these or other solutions are being addressed.

Table II. Impediments to Making NTS a more Cost-Effective Waste Disposal Facility

If the present trend continues and a disproportionate percentage of the low-activity waste is sent to commercial facilities while the higher activity waste is sent to NTS, the average activity level of the waste disposed of at NTS will increase. This will not only result in a higher unit disposal cost for the material sent to NTS but may result in other restrictions on disposal at NTS, such as limits on total activity by isotope.

Although Envirocare is operating as a commercial disposal site, DOE has some responsibility for maintenance and long-term liability for the site. The Envirocare environmental impact statement (EIS) states, "at license termination, the title to the disposal site will be transferred to DOE for long-term care to ensure the health and safety of the public. At that time DOE will become a licensee of the NRC for long term monitoring and maintenance." At the NTS and Hanford facilities, DOE has already incurred the liability for long-term care because these sites were used for the production and testing of nuclear weapons. Additional LLW sent to these well-managed facilities will not substantially increase DOE's long-term liability or create an environmental hazard.

ISSUE

Is promoting shipment of more LLW to commercial waste disposal sites really the most cost-effective option for DOE?

ANALYSIS

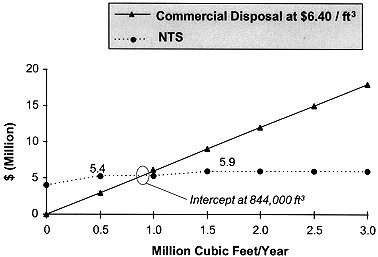

NTS waste disposal operations have the capacity to handle considerably more waste than is currently forecast, with no increase in cost. The base support staff and capital equipment are needed just to keep the facility operational and represent costs that are independent of the volume of waste received. Past experience at NTS has indicated that it takes at least $3 million per year to operate the disposal facilities. The loaded baseline operation cost increases to $5.4 million if the volume exceeds about 300,000 cubic feet, but it then remains constant until the yearly waste volume exceeds about 1.5 million cubic feet. For a waste volume between 1.5 and 3 million cubic feet, the base operating cost increases by approximately $500,000 (for additional staff and equipment) to $5.9 million.

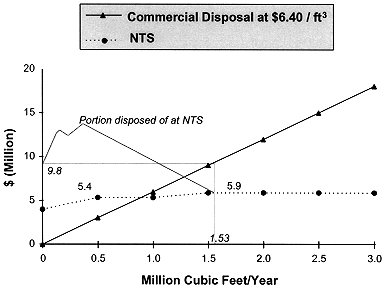

Figure 1 is a plot of the cost versus volume for LLW disposal at NTS and at a commercial site with an assumed disposal fee of $6.40 per cubic foot. As shown on the plot, if all DOE waste is shipped to either NTS or thecommercial site, the total disposal cost is less at the commercial site for a total yearly volume up to 844,000 cubic feet. However, if the yearly waste volume exceeds that quantity, total disposal cost is less at NTS. The greater the volume of waste shipped to NTS, the greater the potential disposal cost savings. For 3 million cubic feet of waste, the disposal cost would be $19.2 million for disposing of all of the waste at a commercial site and only $5.9 million to dispose of it all at NTS, saving DOE $13.3 million.

Figure 1. Cost vs. Volume for LLW Disposed of at NTS and Commercial Site.

The actual savings to the DOE complex that could be achieved if most DOE LLW were sent to NTS rather than to commercial sites depends on the volume of waste generated each year. Table III summarizes three estimates that were used to define the problem. As noted in the table, two of the estimates are from the NTS EIS, and one is from the Waste Management Programmatic EIS (WM PEIS). Case 1 assumes a volume of 15.3 million cubic feet of waste to be managed over a 10-year period, or an average of 1.53 million cubic feet per year.

Table III. DOE Complex Volume Summaries for Waste Requiring

Shipment to Disposal Site

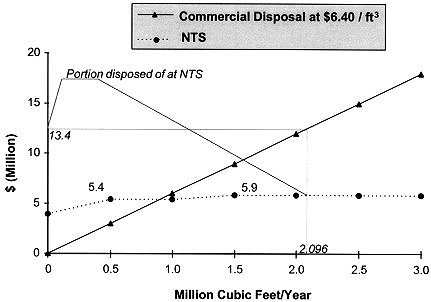

Figure 2 shows the annual disposal cost for the total volume being disposed of at NTS or at a commercial site. It also shows the cost for some fraction of the waste being disposed of at NTS and the remainder at the commercial site. For example, if 0.5 million cubic feet of waste were sent to NTS and 1.03 million sent to the commercial site, the total cost would be $12 million. This is $2.2 million more than the cost of sending all of the waste to the commercial site and $5.4 million more than sending all the waste to NTS. For 1.2 million cubic feet sent to NTS and 0.33 million sent to the commercial site, the total disposal cost would be $7.6 million. This is $2.2 million less than sending all the waste to a commercial site, and $2.2 million more than sending all the waste to NTS. If all 1.53 million cubic feet of waste per year were sent to NTS, the annual cost savings would be $3.9 million, or $39 million over 10 years.

Figure 2. Disposal Cost for 1.532 Million Cubic Feet/Year (NTS EIS Alt.1).

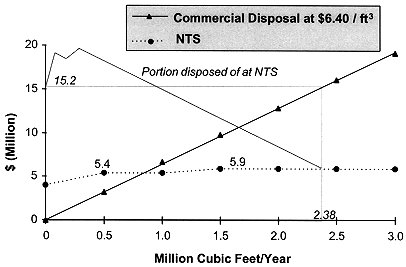

Similar cost-versus-volume plots are presented in Figures 3 and 4 for the yearly volumes of 2.096 million cubic feet estimated in the WM PEIS and the 2.38 million cubic feet estimated as Alternative 3 in the NTS EIS. As would be expected, the potential cost savings for sending the waste to NTS rather than commercial sites is greater for larger volumes. If all 2.096 million cubic feet were sent to NTS, the yearly savings in disposal fees would be $7.5 million, or $75 million over 10 years. For the estimate of 2.38 million cubic feet, the yearly savings would be $9.3 million, or $93 million over 10 years.

Figure 3. Disposal Costs for 2.096 Million Cubic Feet/Year (WM PEIS estimate)

Figure 4. Disposal Costs for 2.38 Million Cubic Feet/Year (NTS EIS Alt. 3 estimate)

DOE's long-term liability for LLW at NTS and at Envirocare has some similarities because DOE will become the licensee for long-term monitoring and maintenance of one cell (and possibly the whole site) at the Envirocare of Utah disposal facility after the site is closed. However, the liability is greater at Envirocare because DOE has not had control over operations at the site. Also, at NTS the LLW disposal area is only a small part of the total contamination resulting from previous nuclear weapons testing; as established in the NTS EIS, testing activities will continue at the site, and DOE will be the responsible landlord in perpetuity. Therefore, DOE has a long-term liability at NTS even without the LLW and MLLW storage facilities, but storage at commercial sites is an additional liability that may not be in the best interest of the government or the taxpayer.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The above analysis shows that changes in current DOE policies and waste management practices could result in considerable cost savings to the government. It is recommended that DOE review current policy in DOE Order 5820.2a on shipment of LLW to commercial facilities and perform a make/buy/return-on-investment analysis of the options. A policy should then be developed and implemented to ensure that a sufficient yearly LLW volume is shipped to NTS to permit cost-effective site operations and low waste disposal fees.

Another option for DOE to consider is directly funding NTS for disposal of DOE LLW and making DOE generators responsible only for transportation costs. As demonstrated in the above analysis, this would result in significant cost savings for the total DOE program if yearly waste disposal volumes exceed 1 million cubic feet.

Some DOE LLW should continue to be authorized for disposal at commercial waste disposal facilities when an advantage to the government is identified, such as lower transportation cost.