INTERSITE TRANSFERS OF DOE WASTE:

EQUITY CONSIDERATIONS

R.. Glenn Bradley

MACTEC, Inc.

12800 Middlebrook Rd.

Suite 204

Germantown, MD 20874

Stephen P. Cowan

EnviroTech Associates, Inc.

7221 Grinnell Dr.

Rockville, MD 20855

ABSTRACT

It has been observed that equity concerns of States that host Department of Energy (DOE) sites may be the Achilles' heel for DOE's plans to engage in intersite transfers of radioactive waste as a means to integrate and optimize its waste management systems and to the achievement of its 2006 Plan1 objectives. In addressing the question of equity it is of interest to determine:

A qualitative review of equity considerations for host States concerning intersite transfers of waste was undertaken and conclusions formulated on the basis of potential incremental increases in health and safety risks and economic impacts associated with such transfers as compared to the baseline risks/benefits resulting from onsite, life-cycle management of all waste generated onsite. The potential health and safety risks to non-host States associated with the transport of the waste are also discussed. A flexible approach for addressing equity considerations with waste management program stakeholders is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The Department of Energy's Environmental Management Program is charged by the Congress with the job of cleaning up the legacy of hazardous materials and surplus facilities from over fifty years of nuclear weapons production for national defense. The primary purpose is to reduce the health and safety risk to workers and the public from these materials and facilities. Since the nation has many other and equally compelling priorities for its resources, the DOE and the Congress strongly desire to accomplish this job at a minimum of cost. This is also the goal of many stakeholder groups around the DOE sites, since they realize that if the job is perceived as too expensive or too politically difficult, it might not get done on any reasonable schedule.

To accomplish as much cleanup as possible and to reduce costs, the Department has proposed the 2006 Plan. Keys to the success of this plan include the need to integrate the cleanup program across the DOE sites, and the need to create a more efficient and effective low-level radioactive waste management system, since most of the uncertainties concerning life-cycle management involve low-level waste. This represents new directions for the DOE's waste management program. The success of the program will depend in large measure on utilization of intersite transfers of cleanup waste in implementing safe, low-cost options. This will, in turn, depend on how the affected parties view the equity considerations associated with the proposed intersite waste transfers.

What should we consider to be an equitable arrangement in connection with proposed intersite waste transfers? Equity, according to Webster's dictionary, is the quality of being fair or impartial; an act that is fair or just. The September 1997 edition of Ecostates: The Journal of the Environmental Council of the States provides a list of elements necessary to achieving an improved environmental protection system. Included was the provision that the system should distribute costs and benefits fairly, accounting for impacts on both present and future generations. This seems like a reasonable objective for our equity determinations.

There are a couple of historical facts that may be useful to keep in mind as we consider the equity of intersite transfers of DOE waste:

INCENTIVES FOR INTERSITE TRANSFERS

Why does DOE feel intersite transfers of waste are necessary? The Department is motivated to invoke transfers primarily as a result of the following considerations:

To help put the need for intersite transfers in proper perspective, it may be useful to examine further DOE motivations for making intersite waste transfers. All of the major DOE sites generate significant quantities of radioactive waste and engage in all phases of the life cycle for managing them, even though some sites may not participate in all operational phases for all classes of waste, e.g., disposal of high-level waste (HLW) and transuranic waste (TRUW). However, none of these sites were selected in the 1940's and 50's on the basis of having favorable environmental characteristics for the treatment and disposal of hazardous materials. Some are located in humid climates and some in arid climates; they have quite different geohydrologic and meteorological characteristics. Moreover, there can be quite a significant difference from site to site in the type and quantity of waste generated by their programs.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the Department is motivated to integrate and optimize the waste management operations across the total complex of site and laboratories, taking into account their respective advantages and limitations for siting and operating waste management facilities. Such a strategy would minimize the duplication of waste management capabilities, provide economies of scale in the treatment and disposal facilities, and facilitate taking advantage of the more favorable environments for conducting waste management operations. With respect to this last point, if the government were prepared to dedicate the necessary funds and time to establish more conservative and costly treatment and disposal capabilities as would be required at selected sites, each major site could undoubtedly be made self-sufficient for on-site life-cycle management of at least the low-level waste (LLW), mixed low-level waste (MLLW), and some TRUW streams and be in compliance with current regulatory requirements. To do so would be costly, both in terms of capitalizing new facilities and the unit cost of operations for those facilities with modest throughputs. This option would also result in significant schedule delays and involve long-term storage of wastes.

We hear and read a great deal about the importance of accelerating the cleanup of DOE sites. The term cleanup is viewed by many to include not only the remediation of contaminated land masses and facilities but also includes the cleanup, i.e., transition to disposal, of the large inventory of stored legacy waste. These materials, if left in indefinite storage, represent an increasing risk over time just as unremediated contaminated sites and facilities would. In many cases, the waste was not originally treated and packaged for purposes of long-term storage. In some instances, the stored materials have not been characterized sufficiently to determine their treatment and disposal requirements. Moreover, the longer the storage the greater the likelihood that the continuity of knowledge about these materials will be lost or obscured. Consequently, some feel a sense of urgency to transition promptly this legacy waste to disposal. Achieving this objective is facilitated by the Department having flexibility in utilizing intersite transfers of waste to put the waste where the appropriate treatment and disposal capabilities exist.

In addressing any equity considerations relating to intersite transfers of waste, we need to answer the questions:

PARTIES AFFECTED

The most obvious parties affected by such transfers of waste are the host State and the host locality for the DOE site designated to receive the waste. The reactions of these parties in the past to such transfers have varied considerably depending on various factors prevailing at the time, e.g., the purpose of the transfer (the storage, treatment, and/or disposal of the waste), the health of the economy at the receiving site, and whether it was an election year. It is not unusual for the positions of the State and the local jurisdiction to be different. The latter, for example, may foresee an economic benefit from the transfer, whereas, the State administration may be under pressure from special interest groups and their news media campaigns to oppose the transactions.

The State and locality that hosts the DOE site from which the waste is transferred are also affected parties. They rarely voice opposition to such transactions unless transfers offsite eliminate operations that would have represented significant economic benefits. They can, however, become quite vocal if such proposed transfers are delayed, thereby putting in jeopardy DOE commitments for achieving certain waste management milestones by specified dates.

Non-host States and their local jurisdictions along the waste transport route represent additional affected parties to intersite transfers of waste. Normally, they are not very visible concerning the issue until it appears DOE has decided to initiate the transfers. Then, concerns are often raised, frequently initiated and fanned by special interest groups, about the risks to the public health and safety associated with the transport of radioactive materials.

Of all the points raised in opposition to intersite transfers of radioactive materials, this one has less substance to support it. However, a traffic accident with the potential for releasing radionuclides to the environment with widespread contamination is a picture the news media can readily conjure up depicting dramatic consequences. This scenario and the realities associated with it will be revisited a little later.

The Department's Environmental Management program and its waste management operations should be viewed as affected parties as a result of decisions on allowing intersite transfers of waste. It is DOE's job to accomplish the program representing the interests of all the Federal taxpayers, i.e., achieve the goals at the lowest cost. The current federal radioactive waste management programs reflect projected schedules, system configurations and funding predicated on flexibility to engage in intersite transfers of waste that facilitate the complex-wide integration and optimization of the waste management systems. Limits on such operational flexibility would seriously disrupt the 2006 Plan and its projected timetable for cleanup of DOE sites. Such adverse impacts could result in significant cost increases which would represent not only bad news for the federal taxpayer, but the impacts would also increase the likelihood of program schedule slippages resulting in a legacy of waste management challenges for future generations.

DETERMINATION OF EQUITY

Having identified DOE's motivations for advocating intersite transfers of waste, lets examine the principal reasons that the stakeholders may resist or have reservations about the fairness of such transactions. The host State and local jurisdiction designated to receive the waste may feel that the acceptance of off-site waste for treatment and/or disposal represents an unfair added health and safety burden for the populace of the region. These stakeholders have generally not objected in the past to the onsite life-cycle management of waste generated on the site. In more recent times there have been instances when these stakeholders have expressed concern about the type of treatment or disposal technologies DOE planned to use but not about the fact that such operations were to be undertaken. The few exceptions have involved proposals for onsite disposal of high-level waste.

Apparently, the State and locality hosting a major DOE site and national laboratory have felt it was fair that the operations from which the region had realized a significant economic benefit over the years should shoulder the burden of risk associated with the management of the waste generated by these operations. For example, the national laboratory in Idaho was for many years, and perhaps still is, the second largest employer in the State. This attitude would imply that these stakeholders would accept as a fair arrangement for "their" site to manage an inventory of waste reasonably comparable to that generated on site, irrespective of the sources from which that inventory is compiled.

A determination about whether intersite transfers of DOE waste represents a fair and just arrangement for the affected parties should be made in connection with a family of transfers from one or more sites to a specific receiving site. An example of where this approach was helpful was in 1995 during the discussions with the State of Idaho over their opposition to the continued receipt of DOE's spent nuclear fuel. Not much progress was being made until the trade-off was considered between receipt of spent fuel for storage and off site shipment of TRUW to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) for disposal. Trading shipments of TRUW to WIPP for spent fuel became a key part of the final agreement.

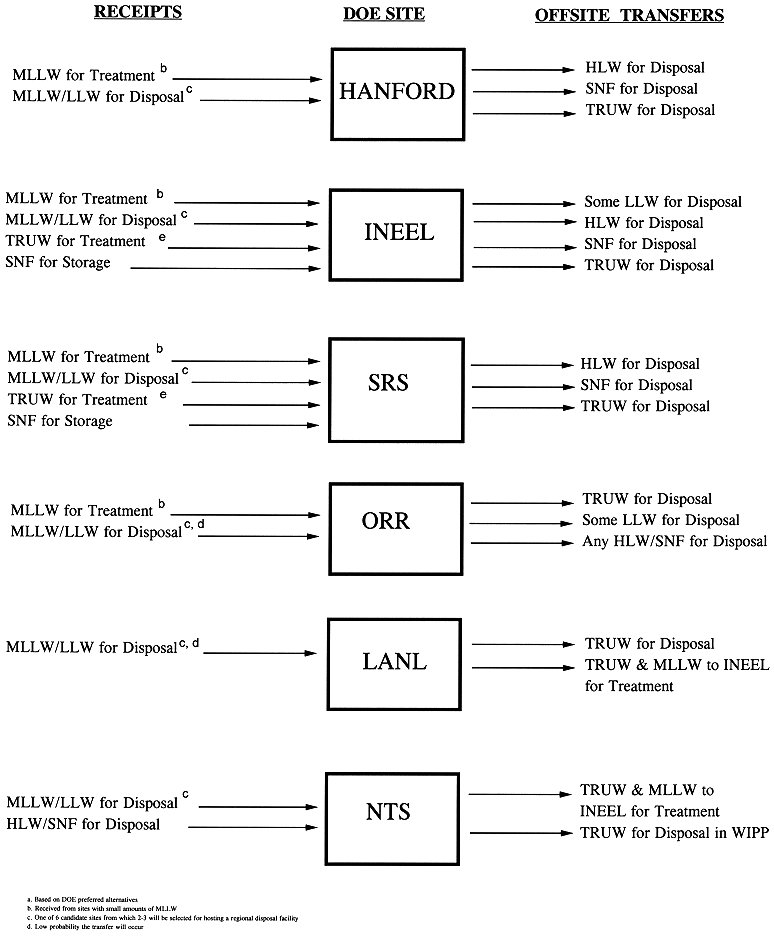

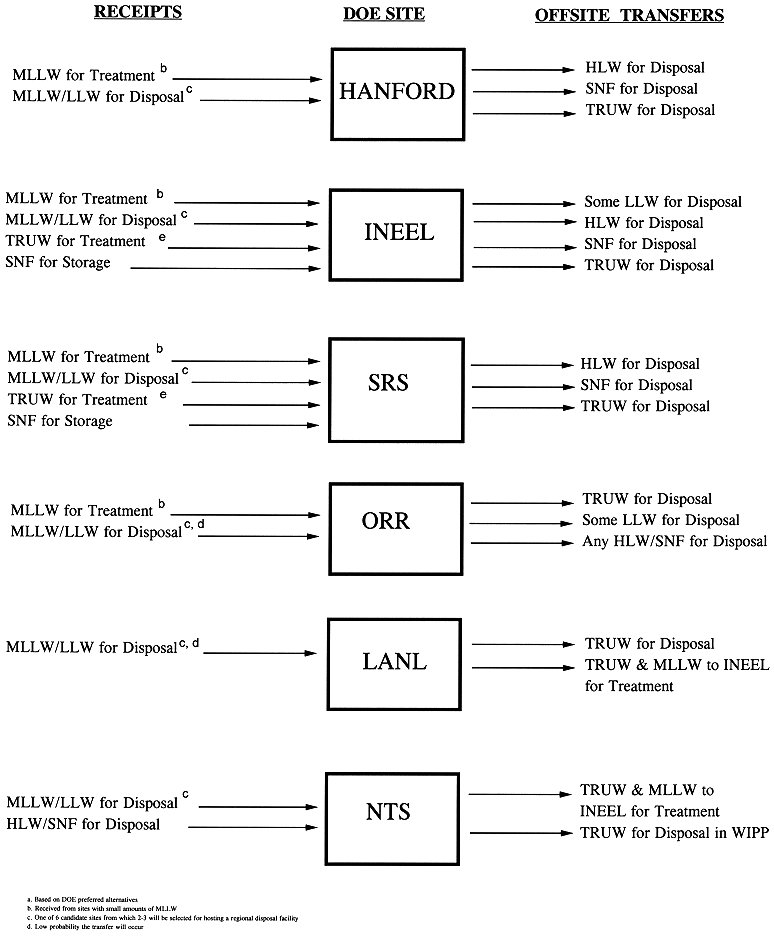

One approach to this process for determining the net waste management burden for a DOE site might be to track the intersite transfers suggested by the DOE-preferred options for configuring the integrated waste management systems, as reflected in the waste management program environmental impact statement (PEIS)2 and the associated Records of Decision. To proceed on this basis would provide a reasonable planning base for DOE to provide integrated treatment and disposal capabilities across the complex. With some exceptions for high-level waste, each major site generates to varying degrees all classes of waste. Therefore, if the different treatment/disposal capabilities for the various classes of waste are distributed among the major sites, it is to be expected that the intersite transfers of the various waste types would tend to produce a level playing field for waste management among the sites, i.e., an inventory of waste to be managed at each site that is largely equivalent to, and in some cases less than, that generated onsite. This redistribution of waste across the DOE complex by intersite transfers can perhaps be visualized by Fig. 1. The various regional treatment and disposal capabilities advanced in the PEIS and depicted in the viewgraph will be decided following consultations with the appropriate stakeholders.

Figure 1. Proposed Inter-Site Transfers of Radioactive Waste Involving

6 Major Sites.

A very important consideration in the equity discussions is the benefit side of the risk/benefit equation. Such benefits would be most apparent in terms of the implications for the overall system, e.g., cost savings by avoidance of duplication of costly treatment/disposal capabilities, lower unit cost of operations through economies of scale, etc. There will also be economic benefits in most cases to the site receiving the waste through jobs directly provided by treatment and disposal operations and, perhaps more importantly, through contributions to the continued viability of the site for DOE's nuclear programs and pursuit of other activities of national interest.

Another consideration that is often factored into equity determinations is whether environmental justice is being appropriately served. That is, would any segment of society be discriminated against or unjustly be imposed upon as a result of the planned intersite transfers of waste. This does not appear to be a relevant factor in these equity determinations in view of the fact that all sites involved have significant inventories of radioactive materials and do not involve elements of society disadvantaged with respect to their ability to bring their views to bear in the decision-making process concerning intersite transfers of waste.

As noted earlier, intersite transport of radioactive materials has been extensive in the United States over the past fifty years. In spite of the many millions of miles logged on U.S. highways in transporting these materials, there have been no fatalities or even significant radiation exposures as a result of traffic accidents and the release of radionuclides from their transport containers. This amazing record is due in large measure to the extensive work conducted over many years by the Atomic Energy Commission, the Energy Research and Development Administration, and DOE in the development and testing of transport packages for all types of radioactive waste. In spite of the extremely low probability of an incident resulting in the breach of the containment for the radioactive material, sophisticated systems are employed for notifying emergency response personnel about shipments that are to pass through their jurisdictions, as well as to provide satellite tracking of the shipments. The DOE shipments of these materials are subject to the Department of Transportation regulations. In addition, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has certified many of DOE's transport casks following a review and analysis of their design and testing data. It is for these reasons that we believe the concerns about transportation of waste materials have been overstated.

HOW THE PROBLEM SHOULD BE APPROACHED

The first step in managing this situation is for DOE to understand what are the "best" options for treatment and disposal of the cleanup waste from the various sites. This should be viewed from a national perspective, but it should not be locked into a single system option. Cost, environmental impact both near and long-term, transportation risk, worker safety and future site use should all be considered to come up with a set of cost-effective options. It will be very important, as will be explained in a moment, for this system to be flexible. As discussed earlier, the DOE's waste management PEIS provides a good foundation for understanding the system options.

It has been suggested a number of times that DOE should get all the stakeholders together and solve the low-level waste disposal problem from a national perspective. DOE has had some success with "national" dialog in the past. DOE and the affected states came up with a strategy for treatment of DOE's mixed waste driven by the Federal Facilities Compliance Act. This strategy involved some intersite transfer of waste but only for treatment. Waste disposal was discussed during this effort but the problem was not resolved. Many people, both inside and outside DOE, now believe that because of the many issues involved, a national discussion to resolve the waste disposal issues is not likely to work.

Therefore, the next step should be for DOE to work with affected stakeholders and solve one problem at a time while keeping the system in mind. For example, if offsite disposal for waste from a site's cleanup is determined to be the best option, then DOE, the shipping site and the disposal host site should get together with affected stakeholders to resolve the equity issues. DOE should bring to the table all the relevant information to be used in the discussion, including economic benefits, environmental issues, transportation risks, etc. An important part of the discussions will be the fate of other radioactive materials on the host site. A site might be receiving low-level waste for disposal and shipping transuranic waste off site, reducing the overall long-term effect. There could be economic benefits to disposal operations. Since the affected stakeholders must convince their constituencies to accept offsite waste disposal, DOE must help them with the argument. Resolving these waste disposal issues one at a time while keeping the overall system in mind will allow DOE to move forward with the cleanup program. Given the number of issues likely to be encountered in a national discussion, if DOE waits to solve the overall national problems before moving forward, progress may be very slow.

CONCLUSIONS

REFERENCES

1. "Accelerating Cleanup: Focus on 2006" (Discussion Draft), DOE/EM-0327, Office of Environmental Management, U.S. Department of Energy (June 1997)

2. "Final Waste Management Programmatic Environmental Impact State for Managing Treatment, Storage, and Disposal of Radioactive and Hazardous Waste," DOE/EIS-0200-F, Office of Environmental Management, U.S. Department of Energy (May 1997).